A co-taught class, the first 50ish years are mostly the focus of Vittoria, while the second 50 are mostly the focus of Raffaella

100 years of Venetian Patricians Women’s Clothing

HL Vittoria di Carduci &

Maestra Raffaella di Contino, OP

This class covers Patrician (ruling class) women’s clothing from 1490-1590. This will cover all the appropriate layers from the skin out and head to feet, highlighting the shifting styles from decade to decade.

Prior to diving in, there are some things that should be clarified regarding the information available. To complicate things from the beginning, there are no known extant Venetian gowns before 1650. Other city states in Italy have a better pool of extant items to draw from. There is the burial clothing of the Medici family, including Eleanor of Toledo. There are also restored gowns in Pisa that are believed to be owned by Eleanor, or her ladies, as well. These items are of Florentine, or a blend of Florentine and Spanish fashion. Unfortunately, being Florentine, the finds, while perhaps informative of common construction methods of the time, tell us little if anything specific about Venetian clothing of the same time frame. This leaves us using visual sources, and the occasional rant by offended dignitaries to piece together what was worn, when.

Like today, there is no one specific “uniform”. There was a range of styles and those were impacted by class, wealth, age, marriage status, and family political alignment. Much like now, fashions changed in a lurching, uneven, manner. New fashions were scorned by the older, embraced by the younger, and despaired of by the Church just as they always have been.

While too large a topic for the scope of this class, be aware that in Venice, as perhaps no where else, you are what you wear. Please note, that in an effort to keep the class at an introductory level, very few specialized garment making or specifically Venetian words will be used. Also, please be aware that this is a work in progress. This class represents what we understand at this moment in time only, and represents our best guesses as to what was worn in our beloved la Serenissima.

1490-1500

Vittore Carpaccio, 1490-1495: Two Venetian Courtesans (also known as Two Venetian Ladies)

There has been extensive debate about the nature of the two women in the portrait. These women are at home in a “private” setting, so they are not wearing the additional outer gown that you see in public setting at this time.

Their body linen is not extravagant, functional in size. The pleated neckline frills show what is possibly a gold/ bronze embroidered edge on both gowns. Both body linen layers also show organized pleats or ruffling at the wrist. There is no visible *proof* to state that these are cuffed sleeves, but that would be reasonable assumption for day to day wearability. An open ended sleeve would be impossible to keep that tidy for three minutes of wear, much less all day.

The sleeves are tied on both gowns in a decorative manner. They are very likely laced up into the shoulder strap of the bodices. The cut of the sleeve itself does not appear to be of a two piece curved sleeve. It looks like the sleeve is cut with an s-shaped sleeve head, and straight down, tapering to the wrist. ( Look at the pattern on the red gown sleeve.) Sleeves are not always solidly connected at the shoulder strap like this. In this era, this is as connected as they get. Also, note the definite contrast between gown body, trim, and sleeves. Nothing matches, but it all coordinates.

Both gowns appear to be velvet, with a silk sleeve. The lady in the rear is wearing what may be a decorative apron, complete with passemetrie or early lace on the bottom edge. The hem of her green gown has a stiffened hemline (likely very similar in construction to the Florentine doppia as demonstrated in the Elanora of Toledo finds – roughly translated as being “doubled”) on the bottom of the skirt. This is clearly shown by the contrast between the smoothly turning stiffened hem, and the fabric collapsing down behind it.

You can also see a pair of platform shoes, now commonly called chopines, near the back of the balcony by the boy. At this stage in Venetian fashion, chopines are about 4-8 inches tall, and wide and boat like under the foot. Later years will see them rise to 18 inches in extreme cases, and become much less clunky under the foot (aka wobbly). They are not often shown in Venetian art, as they were considered underwear. Originally meant to keep expensive skirts out of the muck of Venetian walkways, in time, skirts were lengthened back to to the street level again, hiding the shoes completely. Their function went from being practical, to symbolic, indicative of status. The higher the shoe, the longer the skirt. The longer the skirt, the more money you spent. The higher the shoe, the more attendants you need to walk around with.

Both of them may be wearing false hair. Both women show evidence of the Venetian habit of bleaching the hair to as blonde as possible. The coil on top of the head isn’t tightly twisted. It is soft, loosely taped to the head.

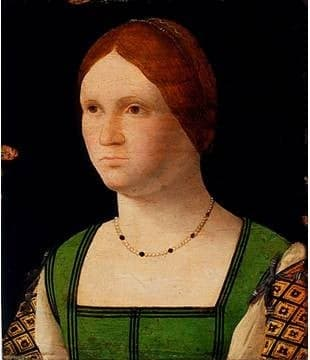

Portrait of a Woman, 1495-98, Carpaccio

Her hairstyle is overall quite similar to the Two Ladies. It is interesting to note that she does not show any signs of hair bleaching.She has far more of the fringe around the face, to the point of it looking like a modern bob. The coil is longer than is normally seen, and due to the very large fringe, thinner in diameter. The extra length may be simply due to the fact that unbleached hair is stronger and less prone to breakage. She is wearing a triple necklace of silver links and one of deep grey pearls. Her body linen appears to be pleatless, perhaps set on a shoulder yoke. This may not be as unusual as it might seem. There is a tendency to assume that all renaissance body linen is built the same way. This is not true, even for what might seem to be identical types of clothing made at the same time, in the same city. In many countries, the Italian city states among them, body linen was made at home, not by a tailor. (fatta en casa) This removes body linen from the system of tailors and tailors training, meaning the homogenizing effect of the tailors profession is completely missing.

In this time, when the volumes of clothing are relatively trim to the body, a non pleated shift would be a very good idea. Ruffles can be added, or not, to plain edges in order to gussy an article of clothing up, while not using much more fabric or adding bulk to the body. This gown is also cut completely off the shoulder, and looks incredibly tight, whereas most of the gowns painted by Carpaccio are the higher boat neck style. The gown itself is relatively plain. No pearls or pleated ribbons here. The fact that her gown is plain, her body linen is left simple, her hair is completely unbleached and unfashionably dark, her jewelry silver, rather than gold, and her body linen minimal may indicate a lower social status, or a lady of exceptional piety, or intellectual interest.

Albrecht Durer, 1495: Drawing of Venetian Lady

Fun fact: Speaking of piety, Durer used this costume study as the basis for the Whore of Babylon in a later print.

Our lady here wears the same taped coil hairdo with the curled forelocks, but is wearing a circlet in addition. The circlet and her necklace may be a set. Her body linen is obviously a pleated style, a functional width, not too much volume, but the sleeves are longer than in the styles above. The body linen neckline may have an embroidered edge, possibly satin, whip stitched, or a couched on cord.

Here, the undergown is not a smooth, evenly supportive looking surface. The gown itself appears to be gathered slightly along the front, under a jeweled band edged in pearls on both sides. This begs the question of whether or not the fashion fabric on the gown is stayed to a solid lining to keep it all in place or not. It looks very “look ma, no hands”, but very seldom is it actually magic holding the bosom up. The very tight belt directly beneath the bosom may also have a part to play in keeping the ladies in place. The center front of the gown is slashed along the center front of the bosom. It appears to be bound on both sides, and extends down to at least the belt at the raised waist. The skirt of the under gown shows a relatively large foliate design. There is no trim showing on the under gown hem. The pattern of the fabric shows all the way to the bottom of the hem, so if there is any hem stiffening present, it was done on the inside of the gown.

The sleeves on this gown are very complicated. Unlike the sleeves of the Two Ladies, these are in two parts. They are tied at the top with a gap for puffing body linen through between them. The elbow ties are also spaced for better poofing results. The parts themselves are well appointed in trim, including what looks like cord couching, or applied passemetrie. Note that the sleeve end of the body linen is plain, no wrist cuff, and it is worn pulled out through the forearm openings in the sleeve.( On occasion, sleeves of this type are very short on the forearm, leaving a ¾ sleeve effect.) This shows us the extreme variety of looks possible within the overall auspices of the style of the day.

The diagonal line across her bosom represents the neckline of her outer gown. You can see the volume of the skirt of it gathered up in her arm, and it seems to be of a lighter and thinner fabric than the portrait above, slightly shorter than the under gown, and of a solid material. The hem on this overgown definitely has a padded and possibly stiffened hem in the form of a padded binding. The train on these over gowns is pointed in the center back. It is constructed using gores set into the side back and center back skirt to fall into a V shaped train that does not pull on the front or even the sides of the skirt. Undergowns, at this time, do not appear to have trains. They seem to be limited to overgowns only, and not every overgown may have had a train. This gown has two giant button like pins or appliques on the front opening holding it closed. These are either very, very, rare, or are something Durer made up. I have yet to see them on any other gowns from Venice at this time. Her chopines are exposed by a good 3-4 inches, keeping the undergown hem out of the mud..

Here are images that show the back of these gowns. Note the very high waistline in back. (check out the hairstyle!)

Gentile Bellini, 1496: The Procession in Piazza S. Marco (detail)

Lazzaro Bastiani, 1494: The Relic of the Holy Cross (detail)

Vittore Carpaccio, 1495: Meeting of the Betrothed Couple (detail)

The “Carpaccio” style is characterized by high waistlines, higher and slightly more boat shaped necklines, on the edge of the shoulder, when compared to the Durer images, and moderately full skirts with occasional obvious hem stiffening. Sleeves, much like in the Durer style, are in one or two parts. The most common types are one part long sleeves, or a two part sleeve with the elbows exposed. Sleeves are often have cut outs in oval or linear “windows”. At times, the sleeve head itself is shaped in a geometric fashion, deviating from the medieval s-shape sleeve head. In this era, “slashing” is a decorative technique used to allow the body linen to be seen on sleeves and occasionally the bodice. At this time, the technique of slashing a fabric to reveal a contrasting lining is not used often. The cutouts do not seem to be raw edged. At this point, applied fabrics used as trim may have a raw edge, but the openings in sleeves and bodices do not. So far, I have found no images showing a similar slash and puff effect on skirts.

Note that since these are images of women outside for a formal occasion, they are wearing the additional layers required for public decency. However, it would appear in Venice, a head covering that hides the hair outside the home is not mandatory at this time. The outer mantle does not appear to be mandatory either. It can be worn as an all encompassing cloak, over the entire body and head, or, more commonly, the mantle is worn diagonally on the body, wrapped or tied over one shoulder, flipped up over the head as needed.

In these details from the Betrothed Couple, we see a plethora of different hairstyles and headwear, several different types of over gowns, and pearls, pearls and more pearls. The detail on the upper left shows what looks to be beading in addition to a row of pearls on the bodice of the black undergown. It also has massive jeweled decoration on the upper sleeve, which also features a decoratively shaped sleeve head. The lower sleeves are covered in easter egg slashing. Her overgown is a v-neck to the waist, and the hem of her train is bound in gold.

The ladies on the right are wearing two different overgown styles, and strikingly different headgear. One wears a medieval oval veil, one a linen coif, and just behind them, a hint of a lady wearing a pearl wrapped coil of hair.

Of interest are the multiplicity of necklaces worn by these two women, and the extremely long belt on the red gown.

1500-1510

In this decade, the neck of under gowns raises to “modest” levels, and becomes squared off, to slightly inclined towards the neck at the shoulder joint.

Gowns themselves are still ornamented, though the categories of things used to ornament them are broadening outward from cloth of gold, velvet and pearls. Trim on the bodice now often runs down the center front in addition to around the neckline, though there is no indication that these gowns are now front fastening. Pearls as a decoration on the gown layer practically disappear. They show up on occasion, but their use is usually limited to the center front of undergowns. Black trim around the neckline becomes much more common, and matching trim often appears on the edges of sleeves.

Sleeve simplify, and change from form fitting and strapped onto the arm, into a loose funnel shape, fitted at the wrist, and smooth at the shoulder line. This indicates that the fullness is cut into the elbow area, rather than the fullness being achieved by using a larger piece of fabric pleated down to fit at the shoulder and wrist. There may be other common sleeve forms in this decade, that simply weren’t commonly painted. Slashing on sleeves may have vanished entirely, or merely have become much less prevalent due to the new shape of the sleeve.

Over gowns, when seen, are almost always v necked, many with attached cap sleeves.

Body linen remains functional in size and shape. It is often not seen at the wrist or neck. When it does show, it is a fine white line. Any pleating is done neatly, tightly, and likely has no released ruffle on the edges. It is possible that the body portions of these undergarments were cut using older t-tunic construction methods to keep down bulk and heat. However, these may be more modern concerns, rather than historical.

Hairstyles have now shifted to the back of the head instead of being on top, and are comparatively tame in comparison to the previous decade. The forelocks remain in many cases, though at times, they are pulled back cleanly into the caul from a center part.

Most examples of head coverings now seem to be of a “cloth of gold”, with either a woven in or applied decoration. Some appear to be hard, cap like. Others most certainly a caul, made of various methods. Jewelry is still diverse, from pearls, to beads and gold chains.

Portrait of a Young Woman- Francesco Pietro Bissolo 1500

Here we have a fine and thin caul worn over dark red hair pulled smoothly back from a center part. She wears no earrings, and her necklace is a mix of pearls and possibly jet or garnet. Her green gown has a high square neckline that seems to cant inward to the neck slightly as it nears the neck. The trim on the bodice extends down from the neckline in three lines, center front, and down the sides of the front, along the outer edge of the breasts. (this outside line will become important in the future.) The sleeves are of a black and gold fabric, cut smoothly at the shoulder. No evidence of pleating can be seen. The sleeves appear only to be tied in place in two spots, front and rear of the shoulder.

Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman, Durer, 1506

If you look closely at this painting, along the shoulder line, you can clearly see that the underlying gown is red, and that the neckline is completely trimmed in black. It is covered by what looks to be a partlet. There isn’t enough of the body depicted to tell just what the Black and White Sheer Shoulder Thing is. It does not fit the shape and style of the overgowns, or neck coverings of this time. Occasionally, a lady might wrap her mantle up around her neck or head, but not over the shoulders coming down in the front. Partlets in Venice do not really show up until the mid 1530s as a specific, tailored, cut to shape item. There is a chance that the item is of German provenance or influence, as Durer moved rather freely between Venetian and German groups living in Venice. The gollar is established in germanic fashion by this time, and this may be a hybrid garment or a gift from a germanic admirer. Her hair is captured in a caul, and her hair is pulled smoothly back, but curls have fluffed up right in front of her ears. Her necklace looks like strips of shell, woven together by a ribbon. The shoulder line of her outfit is neat, and tidy. The tied on sleeves are at least bound in black, if not black in their entirety. Again, only a little body shirt shows at the shoulder. It may be gathered up evenly, but it is not puffed between the ties.

Portrait of a Venetian Woman, Durer, 1505

In this portrait, the forelocks of curled hair remain, though, importantly, the bangs across the forehead have disappeared. Her hair is caught up in a fabric caul, but not as tightly as other examples. Hers, rather than being a “bun cover”looks as if it might be covering pinned braids around the back of her head. Her necklace is a mix of black beads and pearls.

The neckline of her gown is softly square, canting neckwards a small amount. The bodice is decorated with crossing strips of what looks like ribbon. ( possibly selvage strips, or raw edge bias.)The sleeve shows minimal ties, again at the front of the shoulder, and presumably the rear as well. The body linen, which does not show at the neck at all, gathered up at the shoulder, remains unpuffed. The sleeves here might be the same fabric as the bodice, merely left plain. The shoulder ties are black. (The one on the left side of the work is unfinished.) In this image, we can see that the sleeve itself is much looser than in the prior decade. There does not seem to be any pleating at the shoulder to fit the fabric to the shoulder.

Donors in Adoration by Vittore Carpaccio, 1505

Detail is hard to see in this image, however, it gives us important information that we have yet to see in the closer up portraits.

We can see the forelocks, no bangs. She is clearly wearing a necklace, likely not pearls. The neckline of her gown is squared, again with a slight cant inward towards the neck on the shoulder straps. The trim around the neck is also applied down the center front of the bodice. Note that the waistline has dropped to a “high-normal”position. Her sleeves are smoothly fitted at the shoulder, and wrist. Both openings are bound in black that matches the bodice trim. The sleeve is at least double the circumference of the arm at the elbow, tapering back towards the body at top and bottom.

This particular image is often used as “proof”that gown skirts can be different colors in this time. This is the only image with this feature that I have found in Renaissance Venice. I don’t claim to know what is going on with the skirt. Possibilities include an apron, or an overdress of the “suspender strap” style of the next time frame.

It would be quite bizarre to suddenly have a spot in fashion where for a few years, they suddenly used a different fabric for the skirt. Stranger things have happened, however. This image was included because it is the only one I have discovered from this time and place that shows me more than a close up of the bodice and head. Different colored skirt aside, this image is a clear link between this decade, and the styles that come after it.

1510-1520

By the Teens, massive changes in Venetian style have occurred. The fuzzy forelocks and bangs have all but disappeared. Hairstyles become longer, softer, simpler. Blonde to red hair becomes almost required. Jewelry becomes smaller, simpler, less plentiful, pearls in particular almost disappearing.

Two competing styles of bodice emerge. One retains the high squared off neck and squared off shoulder line, mostly side laced. The other style drops the neckline significantly, often to mid to lower bustline and forms a scoop or u shaped neckline. Center front closures appear, especially on the lower fronted gowns. (These low front bodices bear a strong resemble to concurrent bavarian styles.)

Sleeves become massive, heavy, pleated up affairs. Some of them are flat panels, others look to be made of pieced gores. These huge sleeves need giant amounts of body linen to fill them out, so body linen explodes in size, up to 4 times the fabric that had been used a few short years before. Decoration of gowns changes entirely.

Where before, trims were of highly contrasting fabrics, confined to rather narrow edges, and very costly, in the teens, the fabric of the gown itself begins to be used in creative ways. Bands were cut on the straight of grain and fringed, cut on the bias and distressed. Outright upholstery trims like tassels were used on these gowns. Even as huge sleeves became fashionable, cuffs began to appear on them. Solid, plain fabrics become front and center. Brocades and the like did not disappear, but they take a back seat for once.

Beginning in the teens, layers get difficult to pin down. In contrast to earlier, and later decades, the layers of inner and outer become interchangeable, mix and match, modular, in a sense. A lady might be wearing a full gown under the gown you see, and good luck proving it. The old system of inner, outer, coat, goes away. Small shoulder capes appear, in addition to the large all encompassing mantles.

The look is one that tried to be virtuous and plain, but ended up being far more sensual and casual overall. There is less of everything , except fabric itself. That gets piled on till it should be difficult to move. And yet, somehow, in these yards of fabric, Venetian women look even more naked than before.

Titian, Woman at Her Mirror, 1515

Her hair takes center stage, as it is the action of the painting. It looks crimped in nature, which would indicate that it had been braided or twisted while damp and let dry. Note that the crimping goes all the way to her part. This could have been done with a heated iron, but it could also have been done using the double “french” pigtails seen in the first decade discussed. I personally would veer towards using the french pigtail method, as I have yet to see any curling iron type equipment in any of the boudoir paintings. Based on experiments with my own hair, my best guess is two “french fishtail” two strand braids, one on each side of a center part. She has a scarf wrapped around the back of her head.

Her hair shows a telltale sign of sun bleaching, as the length of her hair becomes lighter and redder towards the ends. This is exactly what happens when dark hair is bleached. It turns red first, then to a bright orange, then to a shade of blonde modern women call “ brassy”, then to a softer yellow, all the way to white. It does not appear that methods of “de brassing” hair existed, or, were simply not used. This habit of bleaching also might explain why so many false hair pieces in these paintings are obviously lighter in color than the womans actual hair. To modern eyes, that is a mistake. In this time and place, if you wanted it to look like your hair was super long, you would go buy a lighter length of hair to use. If you bought one that matched the hair up on your head, everyone would know that it was fake immediately, because it doesn’t show the signs of years of Venetian sun bleaching. A good rule of thumb to make modern stunt hair look correct is to make sure it is lighter and warmer in color than your own is. There is no “cool”or “platinum” blonde in Venice.

Her body linen shows clearly how the neckline has broadened and dropped in this style of bodice. This body linen is made to display, made up in a fine fabric, finely pleated, either finely smocked, knife or needle pleated. It is massive in volume, delicate in material. The neckline itself may be ornamented with pleatwork. ( Titian is notorious for hinting at what is there, but not actually showing it clearly. He is an early adopter of working directly on canvas, resulting in a much more atmospheric feel than working on panel. Unfortunately for students of Venetian fashion, this looseness in brushwork becomes a feature of Venetian art, becoming even more prevalent in the later “Tintoretto”years.) It should be noted that body linen in the actual city of Venice, in contrast to the provinces on the mainland, is almost always a white on white embellishment situation, until many years later. There are exceptions, possibly linked to the influence of foreign fashions brought to Venice by those there to trade. (Looking at you, Bavarians.)

Some bodices, such as this one, show a radical shift from the prior decade, as they have lowered and curved dramatically. Note the center front opening. It doesn’t seem to be reinforced, and appears to be closed by hook and eye. There is no modesty placket under the lacing, and the body linen can be seen underneath. The opening continues down into the skirt, at least a minimum of 4 inches but likely more than 8. The bodice line itself is cut on the lower 1/3 if not completely under the breast. The bodice strap at this point seems to be cut as one with the front part of the bodice on a curve. The gown is made from what looks to be a green and gold shot fabric. Not a bit of trim or decoration on this gown, but the fabric carries the look all by itself.

**This may be a “petticoat layer”. In my own experiments, a curved mid bosom undergown helps support the bust, and the extra strap on the shoulder helps keep the massive sleeves from yanking the outer gown clear off your shoulders. I do not know if this is how they were worn, but it makes sense of the evidence presented in the pictorial record. **

For a belt, she has an informal sash tied around her waist, which seems to be completely decorative, as it’s sheer. On her left arm, you can see a draping of bright blue fabric, which may be her over gown.

Titian, Portrait of a Woman, “la schianova”, 1510-1512

First thing to note in this portrait is her hair, which is parted in the center pulled smoothly, but not tightly, down with no forelocks, and caught in a striped gold caul that hovers just above the shoulders. She shows no signs of bleaching at all, bucking the overall trend in hair color.

Her necklaces are thin, and gold. Not a pearl to be seen.

Her body linen is not seen at the neckline of her gown, but she has an informal partlet or sheer shawl tucked into the neck of the gown which may be occluding any edge that might be there. The partlet may have a sheer stripe woven in, but it does not match the caul. At this stage, Venetian partlets are really just lengths of sheer, possibly figured, fabric tucked into necklines rather willy nilly.

The sleeves are hugely voluminous, and open at the front to show the white body linen which is correspondingly massive. The sleeves are pleated into the sleeve head of the bodice, and very likely detachable. The pleating is not robust enough to have the full width you see below, so this would have had to have been pieced, or at least cut in a triangular shape, much like a skirt gore. There is no clue to tell us how long the sleeves actually are, or how long the body linen is in comparison.

The neckline banding looks like an applied band of gown fabric that has been decoratively distressed. It is either on the straight of grain and fringed, or cut on the bias and left to fray. There is no indication of the trim continuing around the neckline. There are wrinkles in the waist area which shows that this bodice isn’t stiffened. She either has an extremely long waist or the sash she is wearing extends down past the waistline of the gown. On close examination, it looks like a scarf or other textile of Middle eastern/ Turkish origin.

Titian, Sketch, Portrait of a Young Girl,1515

The neckline looks very similar to la scianova, including what looks very similar to the distressed band of fabric. The neckline is similarly high, and the sleeve heads feel much fuller than La Scianova, which probably indicates that the sleeves are shorter, but wider in patterning. The sleeve head and bodice straps are very high up on the shoulder, securely on the body itself, not teetering on the edge of the shoulder. It is square enough on the body that it could literally be a bodice from the prior decade in cut.

Her hair appears to be pulled back in some way, but is extremely soft and casual. It may be a length of fabric or scarf wrapped around her hair at the neck, and then pinned to the back of her head. The hatching on the bodice trim band might be to indicate a different color, a folded piece of fabric, or just be how Titian decided to show that the trim was trim, and not a giant bosom wrinkle.

- Titian, Miracle of the Newborn Child, detail, 1511

The detail of this image gives us an invaluable side view to help us better understand this entire silhouette from head to toe. Starting at the top, this allows us to see how the caul is secured. It appears to be pinned into place in the sides and center back, at the crown of the head. This one drapes further down the figure, clearly resting on the back of the neck and upper shoulders.

This angle shows us that the back of the bodice is trimmed, which looks to be the same fabric as the gown itself, combined with thin lines of green. The waistline in back is at the natural waist. She has pulled her overgown train around to the front to hold it up. The hem is heavily embellished, especially for this time frame. The x shaped, quatrefoil trim at the hemline seems to be appliqued silk in a beige or gold. In addition to the quatrefoils and bands of green trim, this hem seems to have The Tuck, an odd feature of gowns in Tuscany. It is likely for hem stiffening, in addition to shortening the hem a bit. This Tuck seems to go all the way around the hem, rather than just the front.

Under the lifted hem of the gown, another skirt can clearly be seen. This is several inches above the ground. This could be for one of two reasons. One, it was cut that length because it was meant to be a underlayer. The other reason could be that she is wearing her chopines, and we simply cannot see them. Note that you don’t see the fabric of either layer puddling on the ground anywhere, other than the train. If the gowns are the same length, then it would lend credence to a “mix and match”system. Whereas a deliberately shortened inner layer suggests the development of a true “petticoat”garment class, which, up to this point, hasn’t been show exist in Venice.

Within moments of introducing these massive sleeves, it seems Venetians added a cuff. Here is the genesis of every Venetian sleeve from now on. There is a larger mass of fabric that has openings, which is then connected to a smaller piece of fabric closer fitted to the arm. We will see this evolve into huge puffed upper sleeves and eventually back into tight sleeves with a tiny puffed sleeve head. This particular sleeve is open along the front, trimmed in green , including matching green tassels. The pleats at the shoulder are again far less extensive than will support the mass of the sleeve, implying that the sleeve is a gored shape, perhaps pieced.

The body linen hanging out the sleeve is loose, not cuffed at the wrist. It is hard to tell if the body linen is actually longer than the sleeve, is pulled through a slit in the cuff, or is merely pulled out the bottom, a la the Durer 1495 gown. It shows in rumpled masses in the openings of the sleeve along the front of the arm. This indicates a large volume pleated down to fit inside the gown sleeve.

1520-1530

The fashions during the 1520’s display a wide variations in sleeve styles, bodices, decoration. The 1520’s build on the changes shown in the earlier decades, with the outrageous usage of materials, including extremely extravagant and voluminous sleeves. The focus is on the fabric and the use of gold, pearls is not seen as much as the use of manipulating the fabrics themselves as the embellishment.

The next step in the development of the “ iconic Venetian bodice” seems to spring from the new popularity of front openings we begin to see in this decade. They are still mostly closed, with a tiny sliver showing. At the very same time, high square necks remain in favor, as do lower mid to underbust cut bodices. All three seem to be worn concurrently, some actually at the very same time.

This is the decade of “more is more, and less is just less.” More than a few images show ladies wearing *two* sets of sleeves at once. Body linen is massive in width and breadth. Even the popular ladies themselves are large. Large, soft, blonde and casually sensuous. The double chin is in.

The problem of “layers”gets worse. I have not found evidence yet that the standard of “not being dressed for public unless you have on two post body linen layers”ever shifted. The type of outer clothing changes, but never the standard. The small shoulder capes persist, but are never a “norm”. There are two possible viewpoints to look at this problem from. One, it is possible that under layers such as the body linen and first layer gown suddenly became so plain and small that no one would wear them by themselves, requiring an outer garment to have any kind of fashion at all, much like the beige and boring underwear we have today. We don’t want anyone to see our cotton undies. The other solution is that they just wore them together as they always did. But, due to the incredible array of styles available at the time under the “fashionable” umbrella, we, from this distance, can’t tell what is outer and inner, because it might change, based on occasion, weather, or even mood.

Hairstyles get beyond casual, up to and including nothing at all other than poofy blonde hair with a flower tucked into it. Big clothes call for big hair to balance out the proportions. The average style appears to have been a simple, large baglike caul that rests on the upper back and shoulders. Some of them do very little to actually contain their hair, acting more like decoration rather than a container.

Palma Vecchio – Three Sisters, 1520

This image is remarkable because it shows you several different variations and styles in the same portrait.

Starting from right to left, you see the sister in a rust colored gown from the side, and that view allows you to see how high the back of the bodice is. It is in line with the bodice strap as it comes over the shoulder, rather high. The next thing to note about this gown is the giant pumpkin sleeves, which are tied in several places with a black cord. The puff comes down below the elbow, and the cuff is tighter fitted and seems to be embellished, potentially by something like smocking or needle pleating. It looks like there maybe shaping in the top lines of the sleeve, at least one seam if not two.

The neckline of the center gown has always been an enigma. Other than * this* image, I cannot find another neckline with a notch in it. However, in the process of preparing these class materials, I noticed what appears to be a front opening on this center gown for the first time. The trim continues across the opening, and up the bodice strap.

This is also a style seen in bavarian fashion of the time, usually expressed as a velvet guard around the neckline on the center front closing gown. What this seems to be is the very beginnings of the Venetian V. In simply leaving the top hook undone, you create diagonal lines in the center front opening, which is only now, in the 1520s, a common bodice style. Combine the idea of a diagonal line with the established center front opening bodices, and you get a slowly expanding deep v neckline.

The sleeve heads are deeply pleated on this gown, perhaps indicating a flat panel sleeve, merely pleated to fit, top and bottom. Note that the pleats are narrower at the forearm. The forearm section has been built out of curved pieces of the fashion fabric, which are laid out with gaps in between them. Those are then stayed to a network of straps underneath them, which in turn have gaps in between them, allowing tiny amounts of body linen to show. At a glance, the effect is one of pearls on strapwork. The wrist section is made of panes of fabric, laid over more of the same fabric, gathered, the ends of which have been fringed or possibly cut on the bias and frayed.

In the third gown, the outer sleeves are pleated not into, but on top of the bodice straps. Presumably, the inner sleeves are attached on the underside. The outer angel wing sleeves are lined in green, and it appears that the inner sleeves are at least partly blue. Her high cut bodice has quatrefoil embellishment that looks to be reversed applique, but may also be a slashed overgarment over a solid undergown of a matching neckline. Here is one of the first instances of making openings in one layer of fabric to deliberately expose a lining layer beneath it, rather than making a hole to pull body linen though.

Palma Vecchio, La Bella 1525

Her body linen seems to be finely gathered, then roughly pleated. There are distinctly two lines of stitching. Notice the lack of jewelry, no earrings, necklaces, chains or rings.

This is a center front tied, or laced dress that is currently being worn “en deshabille”. It appears that she has the dress pulled on over her shoulders, but left completely unfastened.

This is another example of when more than one set of sleeves is worn at the same time. From the outside in, there is a pair of red silk “angel wings” the relative smallness of the pleats combined with the fullness of the sleeves indicates another gored sleeve. The next layer down is a very large royal blue upper puffed sleeve. It appears to not be attached to either the red angel wings, or the red and white inner sleeves. It seems to be lined with a shorter length of black fabric to give the outer fabric the desired puff.

Then we finally have the inner/ fore sleeves, which are pieced together out of red and white. The forearm of the sleeves was pintucked on the straight of the grain, then turned 45 degrees, in order to make diamond shapes without having to pintuck on the bias. The stiff edges on those tucks brings to mind a whip stitch method of making the pleats, rather than a running stitch. At the end, the wrist section shows fabric cut into strips and floated over a gathered or otherwise padded base, similar to the central blue gown in Three Sisters.

Bordone, Venetian Lovers 1525-30

(This is the image that started this adventure. Raffaella saw the painting in Milan, and was very surprised to be able to clearly see black spiral lacing under the white body linen. I saw it online, and had to learn more. Raffaella had a poster of it, and agreed to let me borrow it to stare at. )

Bordone was an apprentice of Titian, but there was a difference in styles. Bordone was a mannerist, and would paint to illustrate a feeling, rather than absolute realism. ( not that Titian was a realist either.) The intent of the artist may come into play later as we explore the more unusual aspects of this image.

The first thing to note is that her hair is still parted in the center, but it is up, cleanly, and has a two strand or fishtail braid wrapped around her head. This is new, for the 1520s. It accurately foreshadows the 1530s. The only jewelry she is wearing seems to be a wedding ring, and the man in the painting is handing her a heavy gold chain, which also seems to be the same as the chain worn at her waist, making this the earliest “girdle” belt we have seen.

The neckline of the body linen is highly embellished with either white work or elaborate smocking. This images gives us the first hint of corseting or an under bodice of some sort, as evidenced by not only the visible black lacing, but by the line of her bosom and how the fabric follows it.

This image poses more questions than it answers, but one thing that it illuminates is that there is at least the possibility of something structural under the displayed body linen. If you look carefully, on the painting right shoulder strap, you will see a thin gleaming strip of cloth of gold. There isn’t one on the other side to match, so we know it isn’t trim. What this looks like is a naughty venetian walking smooth over sumptuary laws and wearing an undergown that is at the very LEAST trimmed in cloth of gold, and hiding it under a plain green gown.

If the outer sheer body linen is actually a partlet, and the lacing belongs to the gold trimmed petticoat under the green gown, then what is painted makes sense. Why would you wear a partlet over a dress rather than tucked into it? This work may be far more fashion forward than its dating of 1525 ish might indicate.

This image also answers a construction question. In the teens the extremely low cut gowns were cut body and shoulder strap in one, whereas this one clearly is not. Under her right arm, at the bosom you can see that the strap goes under the corner of the bodice front. The upper sleeves appear to be very full and still appear to come down past the elbow before the lower fitted sleeve, which now matches the upper sleeve rather than being a contrast. This is another critical change in the evolution of Venetian fashion- as the lower fitted portion is slowly extending, and becoming less elaborate, including being the same fabric as the more voluminous upper section.

1530-1540

One of the most obvious changes of the 1530s is hair. Gone are the soft fluffy blonde poofs. Hair has returned to bondage at the back, crown of the head, often covered by a firm wired structure called a balzo, or hair nets. The balzo can be fabric and embroidered, netted out of goldwork, or created out of false hair, or in a few eye searing cases, all three. The mark of the 1530’s balzos is that the bulk of the fullness is above the ears, whereas the earlier styles wore the fullness lower, sitting on the top of the shoulders and back of the neck, a more structural version of the caul. (The larger lower balzo never caught on in Venice proper as it did in their provinces. Its smaller, higher evolution did finally catch on, near the cusp of the 1530s.)

The ubiquitous pearl choker starts to come into fashion, and will later become much more common. Partlets make an appearance, and will also soon be seen more commonly in Venice. Where before they might have had a sheer bit of fabric tucked into their neckline we now see a fitted partlet, laying smoothly over the shoulders and actually covering skin instead of just being decorative. It is important to note that at this time, partlets normally did NOT come up all the way to the neck, nor did they have a collar. Partlets begin to be worn on the outside of the bodice straps. Pinned in place over the straps, this trick lets Venetian ladies fake an off the shoulder look, while keeping the actual strap up on the actual shoulder, where it is much easier to wear.

Body linen becomes much less voluminous, as the bodice and the sleeves are much more fitted and drive the shape of what would fit underneath. Commonly constructed by pleating onto an embellished band, other variants exist. Occasionally, small bits of reticella and even needle lace appear at necklines and cuffs.

The bodice assumes a decidedly cone like shape, much tighter and involving much more structure. We do not know whether the structure is built into the gown itself, or comes from a separate bodice or “pair of bodies”. There are images in Florentine paintings of the 1530s that show empty gowns holding their shape in the bodice and upper sleeve area. Venetian styles may be the same. Contrasting gown decorations return, mostly in the from of guards on necklines, or down the sides of the new deep v bodice opening. Shoulder straps change position, moving much farther back, almost under the front of the arm. This allows the partlet to lay over the strap, and yet still tuck in neatly to the neckline.

The sleeves continue to evolve in the same direction. Less is now becoming more. Slimmer, less poof, and the poof there is, confined to a smaller and smaller area of the arm. Often, the lower sleeve now matches the upper, though contrasting colors still exist.

Licinio , Portrait of a Woman, 1533

In a radical departure from the softness and casual styles of the 1520s, her hair is almost completely hidden by a decorated balzo. Her necklace is now the iconic necklace of pearls at the base of the throat. Her partlet is of a solid fabric, heavily embroidered in gold. Look closely at her left shoulder. There is the missing bodice strap. Her body linen has a lovely band of whitework on it, extending upwards from the bodice a bit in a memory of the uncovered fronts of the 1520s.

Her sleeves show the new form, being much more fitted for much more of the arm. The once massive upper arm is now a swirl of fabric perched at the very top of the arm. Her waist is marked by a thin gold belt.

- Moretto de Brescia, Portrait of a Lady 15355

This is likely the hairstyle worn underneath the balzos seen at this time. The hair is parted in the middle, pulled back and then braided or twisted around the head. She too has a pearl necklace, with what is likely a detachable pendant.

The new structure that is going into gown bodices is quite apparent here. It looks thick, physically reinforced. It is now quite clear that by the mid 1530s, Venetian gowns were actively shaping the body. The guards are of a deep green velvet, but they do not match the sleeves.

This gown has the new narrow v front opening bodice, which now goes clear to the waist. (This painting appears to have had the lacing painted out. ) The sleeve head is also very fashion forward, in that it is the smallest we have seen so far, just the bodice strap, and then a small sleeve head consisting of small poofs of fabric that is banded in the same fabric as the bodice. The lower sleeves are very fitted, a different fabric and are paned, and are a little longer than the arm, which creates wrinkles, and open up the panes, allowing the body linen to show. This body shirt has to be cuffed, based on the fit of the sleeves of the gown, and the amount that shows through at the shoulder, versus the wrist.

Also note the flea fur, and the handkerchief tucked into the sleeve cuff. She is wearing a girdle belt, but, interestingly enough, no partlet.

Licinio, 1535: Portrait of Arrigo Licinio and his Family

This image clearly shows how the Venetians got the nearly falling off the shoulder look. The strap twists 90 degrees as it leaves the bodice and rises up over the arm. It is set very wide at the front, and then coming in and up at the back at an angle. These back straps are partially covered by the partlet, which is fitted, but sheer and completely plain. In contrast, her body linen s worked with at least white work, if not an application of needle lace.

This gown also shows the conical cone bodice that would require some kind of structure. The sleeves are snugly fitted most of the way up, with the upper sleeves puffed and gathered, but now much smaller. It is unclear based on the image where the lower sleeves are attached, but based on Florentine fashion of the time, having the upper sleeves be part of the bodice, but the lower sleeves being tied in and interchangeable are entirely conceivable.

1540-1550

By 1540, a center front point becomes almost required on any gown, regardless of whether it closes in the front, or back. The point is usually about a hands width, between 3-6 inches down from the waist. The bodice keeps a straight across the bosom, cone shaped silhouette. Interestingly enough, the 1540s sees a relaxation of the relentless march towards tiny sleeves, at least in the fullness of the arm itself. The sleeve cap gets smaller and smaller, till on many gowns, it is no longer a sleeve cap at all. Now, it’s a shoulder decoration. Due to the tiny amount of linen needed to poof between the sleeve cap panes at this time, some of them may just be faked.

The habit of wearing partlets over shoulder straps continues, keeping the small and tidy off the shoulder look going. Partlets are now a required garment. They have developed small standing collars, and some now completely cover the chest. They clearly are now tailored garments with the advent of shoulder seams. They begin to become a focus of embellishment, with every technique known used with glee. Embroidery,, lace, beading, knotting, even 3D appliques, the sky was the limit.

Jewelry begins to return, with most ladies wearing earrings , a pearl choker, and occasionally a very long necklace with a large pendant on it, worn long enough to reach the point of the bodice. Girdles, while they vary considerably in heaviness, material and length, are now almost as universal as the partlet.

Body linen is small in volume, but begins to see hints of lace and more extensive embroidery on it than in the past. Embellishment is still mostly white on white. While it is foolish to make blanket statements, it would make sense that most boody linen at this point has cuffed sleeves with ruffles added. This doesn’t mean that open sleeved body linen wasn’t worn too, and likely was if the sleeves were not going to be worn. The best way to tell is to check the wrist. If the ruffles are “ just so” and perfectly even, that is very likely a cuff hiding under the sleeve.

- Lorenzo Lotto 1544, Portrait of Laura de Pola

Here we see a vestigial balzo, now almost a little cap, covered in embroidery or bullion work that matches the partlet. Her hair is parted in the middle and has the tiniest little twists of the hair on either side.This is the beginning of the twists that eventually become the iconic horns.

The partlet seems to be bullion work on top of fabric, also of gold. If that partlet is actually gold work, it would explain why she seems to have a second fabric partlet on underneath it, which is unusual. Between possible scratchiness, and the need to protect the gold from skin oils, a layer of linen in between makes perfect sense.

It is unclear whether the body linen we see is a masculine shirt style, or if the top is an unseen, more feminine style, and what we see is actually another partlet. At the cuffs off this gown,you can see actual closures! These become more common in later decades as the sleeve continues to tighten down on the arm.

All of the black embellishment, on the entire gown is appliqued by hand. The tops of the sleeves now have just the slightest hint of a poof, and the rest of the sleeve is very fitted. It looks like the gold partlet is pinned out on top of the shoulder straps as per usual.

Accessories include a new very common pearl choker, as well as a feather fan, which is attached to a very robust gold girdle belt.

Titian, 1545, Portrait of Lavinia

Here is slightly more elaborate, classic mid century Venetian hair. She wears a small curled fringe in front. These would be “bang”length when uncurled. The bulk of her hair is tightly braided and wrapped around her head at the crown in back, not the middle of the top of her head. In addition to earrings, she wears the essential pearl necklace nestled in the collar of her partlet. The standing collar of her striped partlet carries a small tidy ruffle. There is an obvious shoulder seam at this point in time. It appears to still be worn over the shoulder straps of the gown.

The center front point is down to about 4 inches from the natural waist. This gown may have a center back point as well.

It is ladder laced with a tone on tone cord, and clearly has some kind of structure to keep the whole affair from wrinkling, and to give it that structured cone shaped silhouette.

Body linen here is going to be strictly functional in size, as the bodice and sleeves are going to require that there not be excessive yardage. The sleeve cap here is just a vestigial poof, slight bits of body linen showing. The actual arm of the sleeve softer than what we saw in the 1530s. The far shoulder shows the form off the sleeve cap better. It is paned, and by this point, the puffs of linen between them may be faked. er sleeves are loose enough to allow for some volume, so either option may be in play. Likely, the body linen has a wrist cuff, as the ruffle is tight, small, and regimented.

In addition to the required choker, she is wearing the new style of necklace, thin and long enough to come all the way down to the waist point. Heer girdle is thin and delicate, and of indeterminate length.

Bordone, 1545-1550, Portrait of a Lady, traditionally of the Fugger family

Again we see tidy and compact hair, with a center part, and more of the twisted or spiral curls on either side. now with more volume, and then up and in several rows of braids in the back, real, or possibly a very good false as the color isn’t a perfect match, but lighter and warmer, just as it should be.

The partlet seems to be made nearly entire of reticella lace, which would have made it exorbitantly expensive. Also of note, the partlet completely closes in front like a shirt, completely covering the chest. Look closely and you will see the red of the straps showing through the delicate lace.

While the bodice retains the very structured cone look, it looks casual due the extreme shininess of the fabric, which gives the appearance of wrinkles. This is clearly a fashion fabric over something more structural.

The sleeve heads are unusual, as it looks like the material on the sleeve head looks either knotted or otherwise compacted, and there are two layers, of differing types. There is still looseness around the elbow, enough for fully flexing the elbow without constriction. The ends of her sleeves actually have a pleated in ruffle. It’s unusual at this time for otherwise regular outer sleeves to have embellishment near the cuffs.

The center front opening clearly extends down the front of the skirt, which falls in luscious folds from the waist. She is wearing a girdle belt, and it hangs down, but the tail is worn off to the side, not down the center.

She wears a ring on each hand, however, no pearl necklace, and no earrings.

Onto the next decade 1550-1560- Transition into the iconic Venetian look

Cesare Vecellio, Venetian noblewoman in mourning, 1550

From “De gli Habiti antichi et moderni di Diverse Parti del Mondo” 1589-90

Portrait of Countess Olivia Porto, Veronese, 1551

From head to toe-

Her hair is dark, not obviously lightened. She wears it high on the back of her head, neatly pulled back, with only a hint of friend. The caul or cap on the back of her head is heavy in goldwork. It may even have jewels set into the front edge like a headband.

Her earrings are large pear shapes pearls on gold ornamented wires. She wears the expected pearl choker, along with three rings. Her girdle is of the large chain and ornament variety, terminating in a flea fur with gold fittings.

Skin out analysis-

Body linen is barely seen at the neck, in a small and sheer ruffle. Her partlet appears to be sheer, and ornamented with what look like gold bows. The bodice shape shows the development of the center front point, but remains in the 3-4 inch range. Importantly, the waistline sits naturally on the waist at the side waist, rather than pulling upwards slightly as some do to increase the illusion of depth. She may, or may not be wearing a supportive underbodice or corset. The bodice shows the faintest hint of a bosom, and a touch of wrinkling on the body left, which would be in keeping with a softly boned, or quilted underbodice, rather than a reeded style of corset. Due to the presence of the over layer, the interaction of the sleeves, bodice straps and partlet cannot really be determined, other than to say that they must be slim, and any embellishment at the shoulder small in scale. The gown skirt has a casual gathered to the bodice look. The fabric itself might be shot red and gold. There are spots of shimmer all over the garment. The skirt hits exactly at the floor. Her overcoat is a study in magnificence, with couched and embroidered gold decorations on the exterior of the silk, and lined in fur. There do not appear to be any closures on the coat. Note the very full cut of the coat. It expands rapidly into a wide triangle, calling to mind Turkish caftans, and, the immensely influential Spanish fashion of Eleonora da Toledo. There is an interesting bit at the body left shoulder. At the shoulder seam, there is what looks like a pleat in the upper sleeve. There are obvious gathers in the sleeve head in the front side of the arm, and yet, the sleeve is not draping from the arm at all. The form is close to the arm, just loose enough to allow for free movement.

Her daughter wears a gold cap, gold chain necklaces, and a girdle. Of interest is the gold trim on her dress. The position at the hem of the dress is “ standard”, but look at the matching stripe of gold on her sleeve. It continues all the way down to the wrist, encircles the wrist, and comes back up her arm on the underside. That, not being a typical trim placement in Venice, suggests that her gown may have been recut and altered to fit her. The trim would be applied over the seams of a two part sleeve, and perhaps elongated by the gold at the cuff. Also, note the deep vertical seams under her arm. This looks like a gusset, added for fit.

Her body linen shows only in a thin white line at the wrist, and a few points of needlelace at the neck. The bodice strap is ornamented with pearls and gold, which continue across the front of the bodice.

However, this interpretation raises more questions. If it’s not her best dress, then why is she wearing it? If this is her best dress, then is she the youngest? If this is a new gown, why does it have such odd sleeve trim, while so much of the gown matches up stylistically with her mother’s outfit?

Portrait of a Lady in White

Titian, 1553

Head to toe-

Hair is up, neatly to the upper back of the head, where it is ornamented with what may be a gold/pearl cap or call.

There is a curled fringe all the way across the front hairline to the ears. Her hair may be lightened, as both her eyes and eyebrows are dark.

Her earrings are very large pear shaped pearls on gold wires. While it is often difficult to tell whether a painter means to show you cosmetics, or a naturally flawless female, in this case, it can be relatively safe to assume that there is at least a touch of carmine to the lips and cheeks.

She wears the now popular matching bracelet set, one ring that can be seen, and carries a flag fan.

Skin out-

Her body linen may be showing at the neckline in a relatively hefty pleat. The wrist ruffles are even enough to entertain the idea that perhaps they are ruffles added to an unseen cuff. At this point, it would seem that venetians are looking to reduce bulk in all layers, including body linen. It would make sense that for ease of wearing alone, the less you are strapping down again the skin, the more comfortable it will be. It is not clear from this painting, but the fabric showing in the center opening could be her body linen. It could also be a stomacher. It could even be a corset. This lady is slightly built, quite dainty. However, in wearing, lacing directly over a pleated linen shift does not give you that flat and perfectly smooth look. There is obviously some form of boning on either side of the opening. However, that does not preclude the presence of a “hold it all together” underbodice. Note that the point now extends down to the pubic area,at least 6-8 inches. This alone would necessitate some reinforcement of the bodice opening to avoid shifting and gapping.

Of interest is the waistline, and center front of her gown. Rather than a standard girlde, her waistline is decorated by what look likes all gold buttons or studs. They continue down the front of the skirt, holding two finished edges together. This is one of the few gowns we see in Venice with a center front opening. Note as well the random, attachment of the skirts to the bodice. The skirt looks to be gored, rather than a flat panel gather. There isn’t that much fabric at the waist, and what is there isn’t attached evenly.

The angle of the pose keeps us from telling whether or not the partlet is being worn over a bodice strap or not. From this angle, it almost looks as if there isn’t a shoulder strap at all. That may have been the look they were going for, as partlets were worn over them in decades past, giving a much more off the shoulder look. There is, at the very top of the shoulder, behind the puffs, the smallest hint of a shoulder strap. There appears to be a shadow line at the top of the strap possibly indicating that the partlet is not being worn over a strap.

The sleeve has a row of puffs at the very top on the edge of the bodice strap that may be faked. Then, there is a small paned upper sleeve that looks to be pleated in to fit, rather than cut in a smooth curve. Beneath that, there is a twisted cord laid down, held at intervals by the same gold flower heads as decorate the skirt and waistline. Under that is a band of needle or bobbin lace. This particular pattern looks very modern, a boon for anyone wanting to make a replica of this gown. While there is no visible seam,the sleeves behave like a two part sleeve. The end of the sleeve is covered by the bracelet, so any closures there are hidden.

Titian- Girl with a basket of fruit, 1557

Head to toe Our young heroine wears pearls twined into her bun, pinned high on the back of her head. In addition, she wears a diadem, set with pearls and other gems, terminating in a forehead drop of a set jewel, and a pearl. The forehead jewel sits in line with the line with the curled bangs. Her earrings are rectangular, dark blue or grey, and hung from wires. Her necklace is very likely the standard choker. Note though, there’s no obvious clasp in back. Her only other obvious jewelry is a ring, and a ornate girdle, which appears to be seen in place. Skin out- Body linen shows at the slashed upper sleeve, but not between the shoulder strap and the sleeve head. The cuffs on the body linen are quite interesting. The shift sleeve is a simple expanse, close to the arm, certainly not full enough for a full on 3 times width pleated on sleeve. It is an educated guess to say that the body linen here has tapered sleeves that may be much fuller at the top, but considerably slimmer by the time it gets to the wrist. The cuffs are definitely an added ruffle that may have needle or bobbin lace on it. There may be hook and eye closures on the body linen, or the gown sleeves themselves. The body linen showing from the back neckline has a ragged appearance, usually the result of adding flat panel lace to a three dimensional neckline. Of special note, we have a partlet worn en dishabille. This lends credence to the theory that earlier partlets were literally merely strips of fabric wrapped around the back to the front and tucked in. This one has a very “crunchy” texture, equivalent to an organza in modern weaves. There may be a woven in pattern, but it looks mostly devoid of decorations. The back view allows us to see a Very Venetian Thing; The center back bodice point. It does not show up 100% of the time in the few rear views we have of this time frame. However it may be safely assumed that a “normal” Venetian gown of this decade, all the way out to 1600, have a back point and center front point. The sleeve heads appear to be slashed and self-bound. There is a very fine line of slightly lighter color around each slash. The sleeves are otherwise undecorated. This may be to allow the fabric itself to do the talking.

Vecellio, dress of Venetian women, 1550? (This drawing is dated by the author to be “dress at 1550”. I believe this to be late 1550s, if not 1560-61. )

Head to toe- Her hair is dressed very high at the crown, and covered by a lace edged veil. There are very defined curls at the front, but they are still curls, not a roll, nor a suggestion of horns yet. Her most obvious necklace is a pearl choker with a pendant that sits inside the partlet neckline. The second is a heavy gold chain that sits outside the partlet collar. That arrangement becomes common in later years as partlets develop a standing collar. One ( the shorter, usually pearls) necklace inside, one ( usually much longer, material varies between pearls, combinations of chain and pearls/gems, and merely gold chains) outside. The long ones tend to get tucked into the laces of front opening gowns. If you walk with a very long (below waist) pendant necklace, while wearing a boso binding gown, it will bounce back and forth across your torso while you walk. Natural, but unattractive for sure, and that would never do. The outer necklace also helps prop up the neck ruffle. Popping your collar, 1550s style. Also important to note: Venetian partlets almost never actually cover the bosom after about 1550. They usually leave the strip from the chin down to the gown bodice uncovered. She carries her right glove in her hand, the left is worn, and rings worn over it. There is a hint of what might be walking platform shoes peeking from under the skirt. Skin out Body linen doesn’t show in this image. Her partlet has a high , ¾ round collar. There does not appear to be a stand on the neck. The ruffles seem to be bound directly to the neckline. It is decorated with flowers that may be anything from applique shapes of cloth of gold, embroidery, beading, or woven in pattern. Of special interest are the white triangles on the bodice neckline. That could be applique lace. It could be fabric tabs. It could be the neckline of the body linen flipped down over the exterior of the gown. Note that the gown hemline is shown as being dagged or pinked, perhaps a shaped facing. The sleeves are simple, a band of piping or cord at the seam, with panes curving over fluffed line to the shoulder. They do flaunt a flipped back cuff of needle or bobbin lace. This may be directly attached to the gown, and no longer be part of the body linen. There is almost no shoulder strap to be seen. This could be from wearing a solid partlet over it, or minimizing the width of the shoulder strap. (A partlet worn over a wider strap would be more comfortable, and I lean that direction.) The gown skirt is attached to a very deep v in small gathers. You can also see the very beginning of the extra “lift” to the side waistline to create both a deeper v, and a more dramatic skirt.